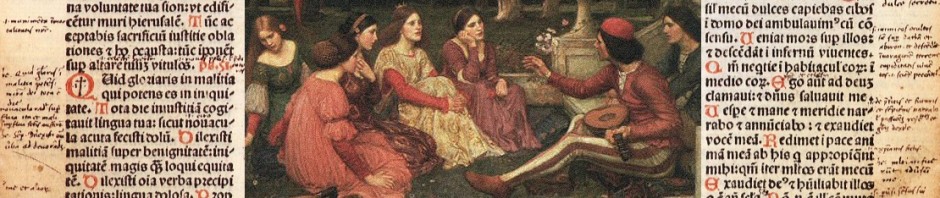

Rick Blaine: “I stick my neck out for nobody.”

Casablanca's Rick Blaine

Nothing less is at stake in the film Casablanca than the very course of the war. Victor Laszlo arrives in Casablanca, as man on the run from the Nazis and a crucial voice in the war effort. We are never really told why Victor Laszlo’s role against the Axis is so critical. We know that he was an intellectual and Resistance leader who escaped from a concentration camp and is held in such high stature abroad that the Nazi’s are afraid to kill him outright. In this sense he is much like Nelson Mandela, 2010 Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo and other leaders imprisoned by totalitarian regimes to afraid to kill them, but also too afraid to let them speak freely. We are given to believe the Laszlo’s leadership is essential to the struggle against Fascism, and there must escape to America.

The central character in the film is Rick Blaine. Blaine is a cynical, self-centered loner. Embittered and disillusioned, any purpose he once had in life was snuffed out when the love of his life abandoned him. He has retreated to Casablanca, the ultimate neutral in a place famous for neutrality. But early on in the film we are given clues that deep inside Rick Blaine there still beats a hero’s heart. The question is can he find a reason to cast aside his comfortable, isolationist existence and once again take up the fight against Fascism. Rick is the one person who has the power to help Laszlo, for he has come into possession of letters of transit which would allow Laszlo to leave Casablanca for Portugal and the Americas.

From early on in the film we are given clues that Rick Blaine’s isolationist attitude is a carefully constructed self-defense mechanism. He refuses to drink with customers. He repeatedly refuses to help people. “I’m the only ’cause’ I’m interested in,” says Rick. The character of Captain Renault tells the German officers that Rick is decidedly neutral, and when Major Strasser probes, Blaine displays a devil-may-care attitude that seemingly confirms it: “What is your nationality?” asks Strasser. “I’m a drunkard,” replies Rick.

Major Strasser: Are you one of those people who cannot imagine the Germans in their beloved Paris?

Rick: It’s not particularly my beloved Paris.

Heinz: Can you imagine us in London?

Rick: When you get there, ask me!

Captain Renault: Hmmh! Diplomatist!

Major Strasser: How about New York?

Rick: Well there are certain sections of New York, Major, that I wouldn’t advise you to try to invade.

To most, Rick seems decidedly non-committal about politics, life and love. “Where were you last night?” asks his lover Yvonne:

Rick: That’s so long ago, I don’t remember.

Yvonne: Will I see you tonight?

Rick: I never plan that far ahead.

But we see the chinks in Blaine’s armor. Near the beginning of the film, he refuses entry to the bar’s back room to a high-ranking German official, and it’s obvious he has no love for the Reich. We learn that before coming to Casablanca, Rick was a gun-runner and partisan in the war against Facism:

Captain Renault: In 1935, you ran guns to Ethiopia. In 1936, you fought in Spain, on the Loyalist side.

Rick: I got well paid for it on both occasions.

Captain Renault: The *winning* side would have paid you *much better*.

Renault goes so far as to call Rick a closet “sentimentalist.” But what could motivate him to cast off his façade and ‘return to the fight?’

Deep inside Rick Blaine still believes in the ideal of love. Annina asks him, “Oh, monsieur, you are a man. If someone loved you very much, so that your happiness was the only thing that she wanted in the world, but she did a bad thing to make certain of it, could you forgive her?” Rick replies from behind his façade: “Nobody ever loved me that much.” But he helps her, arranging for her young husband to win at roulette to gain the money for exit visas.

The return of Ilsa Lund is the critical motivator. The woman who destroyed his soul has returned. He still loves her, and he despises her. She is the reason he has cut himself off from the world and sheltered himself from the ideals he once held so dear. Drinking himself to a stupor after their first meeting, Rick asks Sam a question that foreshadows the eventual outcome of the film and is also a revelation as to what this story is really about:

Rick: If it’s December 1941 in Casablanca, what time is it in New York?

Sam: What? My watch stopped.

Rick: I’d bet they’re asleep in New York. I’d bet they’re asleep all over America.

December, 1941, is when America was jolted out of the ‘sleep’ self-imposed isolationism by the attack on Pearl Harbor. “Casablanca is, among other things, a fable of citizenship and idealism, the duties of the private self in the dangerous public world. It is a thoroughly escapist myth about getting politically involved.” (Time).

Rick Blaine suffers no such blatant attack. Instead he transformed by a series of reminders about the true nature of love and sacrifice. First, Annina offers to sacrifice herself for Jan, and he remembers the nature of love. Then he learns that Ilsa was married to Victor during the time they were in love in Paris, but she thought Laszlo was dead. Ilsa tells Rick that she loved him with all her heart, but that in Laszlo was a higher purpose she could not abandon… and Rick relearns the nature of sacrifice for ideals. When Laszlo attmpts to force a political confrontation Rick’s Cafe by asking the band to play La Marseillaise to counter the singing of the Nazis, Rick nods his approval. (Click the picture to go to the scene.)

Victor Laszlo has reminded Rick of the power of belief in a cause:

Rick: Don’t you sometimes wonder if it’s worth all this? I mean what you’re fighting for.

Victor Laszlo: You might as well question why we breathe. If we stop breathing, we’ll die. If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die.

Rick: Well, what of it? It’ll be out of its misery.

Victor Laszlo: You know how you sound, Mr. Blaine? Like a man who’s trying to convince himself of something he doesn’t believe in his heart. (Click the picture to watch the scene.)

"You sound like a man who's trying to convince himself of something he doesn't believe in his heart..."

Finally, when Laszlo pleads with Rick to take Ilsa away to America, willing to sacrifice himself for love once again discovers the nature of idealism, love and sacrifice:

Victor Laszlo: “You won’t give me the letters of transit: all right, but I want my wife to be safe. I ask you as a favor, to use the letters to take her away from Casablanca.

Rick: You love her that much?

Victor Laszlo: Apparently you think of me only as the leader of a cause. Well, I’m also a human being. Yes, I love her that much.”

In Laszlo, Rick sees a better version of himself; Laszlo is the man Rick might have been if Rick had not abandoned himself to self pity and isolationism. In the end it is Ilsa who is tempted to surrender her ideals, and the newly revived Rick who tells her: “You’re part of his work, the thing that keeps him going. If that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life.” He speaks from experience, with the voice of the man who has been hiding behind the now broken façade of indifference.

“Victor and Rick are splintered aspects, it may be, of the same man. Ultimately, the ego rises above mere selfish despair and selfish desire. It is reborn in sacrifice and community: “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill o’ beans in this crazy world.” (Time).

Rick Blaine is a multifaceted character. We see three different personalities during the course of the film: the heartbroken, cynical isolationist, the joyous, carefree lover, and the idealist dedicated to democracy. But because of Rick’s mysterious nature and the depths of despair to which he has fallen, we are uncertain until the very end which character will emerge victorious. Will selfishness prevail and send Laszlo (idealism) to his demise? Or will Rick choose to remain safe behind her carefully constructed façade and doom Ilsa and Laszlo to an eternity in Casablanca?

In fact, Blaine has good reason not to act at all. He respected in Casablanca. His bar is popular and by all appearances he lives quite well. In addition, by doing nothing he might very well have his heart’s (at least his cold heart’s) desire: Ilsa. The Germans discuss the fact that they cannot let Lazslo escape, nor can they allow him to remain in Caablanca. “You have already observed that in Casablanca human life is cheap,” says Major Strasser. Should Rick stand aside and refuse to help, Laszlo will meet the fate Ilsa thought he had met in the concentration camp. And Rick would have Ilsa.

But it is Major Strasser who pays the price when Rick recovers his idealism and helps Laszlo and Ilsa escape (click the image to see the final scene of Casablanca):

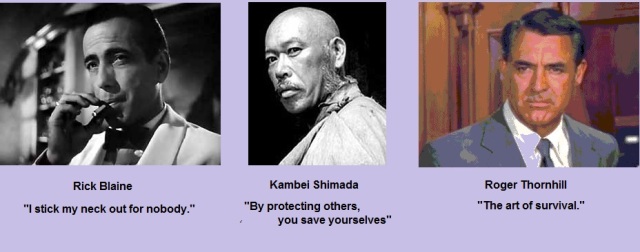

Kambei Shimada: “By protecting others, you save yourselves.”

Casablanca is a rich and complex film, and Rick Blaine is among the most complex characters in film history. By comparison, Seven Samurai and its cast of warriors seem so much simpler. But not for long.

The story appears straightforward: A town ravished by bandits hires seven masterless samurai to protect them. For the peasants in the village noting less than survival is at stake. They are already reduced to eating millet. If the bandits come again, stealing their new crops, taking their women, killing their men… the village will simply cease to exist.

But there is far more beneath the surface of this film. Just as Casablanca can be seen as a parable about America’s birth from isolationism during World War II, Seven Samurai is about the strict class structure of feudal Japan and the beginning of the end of the Samurai class. For the six samurai (and one wannbe) hired to protect the village the survival of their entire way be being is at stake.

There is also the question of just who is the central character in the film. It could be argued that all seven represent one unified character, various aspects of the noble ideal of the samurai way and what it has become. Another analysis claims: “The story is not about the samurai themselves nor the attacking bandits, but the story of the peasant hero Rikichi. Rikichi is a young farmer who has first voiced out on fighting the bandits. Everyone in the village is in despair, ready to yield to the bandits when they arrive, but Rikichi vows not to surrender anymore.”

But whether it is the peasants or the samurai, the spirit of one noble man brings them together: Kambei Shimada, the masterless samurai first seen pretending to be a monk to save a child being held hostage. In this very first sequence we see Shimada’s idealism to the samurai code: Justice, Bravery, Benevolence, Respect, Honesty, Honor, Loyalty. (Oriental Outpost). As we meet him he is having his topknot shaved off so he can impersonate the monk. The topknot was a significant status symbol to a samurai, as much a part of him s his sword; that Shimada would have it shaved represents his dedication to the code. (Astell).

When the villagers set out to find “hungry samurai” who might agree to protect them, they at first find class-conscious oafs who cheat them. Such is the state of the noble warrior class during the years of endless civil war. Then they find Shimada. Shimada may be a masterless, but he retains the idealism of the true samurai way, and agrees to help them. He decides seven samurai will be needed to protect the village. His recruiting is a mixture of cunning tests of skill and appeals to the sense of honor and justice of the true samurai. He admits to the recruits the farmers have nothing to offer but rice.

Kambei Shimada: As a matter of fact, I’m preparing for a tough war. It will bring us neither money nor fame. Want to join?

Shichirōji: Yes!

Kambei Shimada: Maybe we die this time.

Shichirōji: (smiles)

We learn Shimada, like Rick Blaine, has a long history of fighting on the losing side. “You’re overestimating me,” he says. “Listen, I’m not a man with any special skill, but I’ve had plenty of experience in battles; losing battles, all of them. In short, that’s all I am.” But we know he is much more. He is a symbol of the true samurai way, and he manages to find samurai who will defend the village. In fact, Kambei is such a noble example of samurai that two warriors he tries to keep away are compelled to follow him: Katshuhiro -the young man who is seeking an ideal, Kikuchiyo, the peasant who wants to be a samurai.

But Simada’s path is far more than a journey to a seemingly hopeless battle. It is a path of discovery. When the samurai arrive the villagers hide, afraid the warriors will plunder their homes and take their women.

The villagers, victims of the ruthlessness of all sides during the years of civil war, see the samurai as just another kind of bandit. Shimada sets out to build trust between the samurai and the villagers, developing a strategy for defense and overseeing the martial training of the village men who will assist in the fight against the bandits. But another event brings Shimada once again to the realization that the samurai are not held in the high regard they once were and, in fact, are threatened.

A cache of weapons is found, leading to the discovery that the villagers have killed and robbed samurai fleeing from nearby civil war battles. Kikuchiyo –who we know to be a peasant and eventually learn is the child of farmers killed by bandits- heatedly explains the farmers’ actions:

“They’re nothing but stingy, greedy, blubbering, foxy, and mean! God damn it all! But then who made them such beasts? You did! You samurai did it! You burn their villages! Destroy their farms! Steal their food! Force them to labour! Take their women! And kill them if they resist! So what should farmers do?”

The day of the ideal samurai –if indeed there ever was one- are over. Kambei Shimada begins to learn the tragic lesson – he is a relic of a bygone era, cling to a code others have long abandoned.

When the climactic battle comes, Kambei leads with calm precision. He is the consummate warrior in the samurai way, skillful, wise unselfish. He leads his ragtag band of castoff swordsmen to remarkable heroism and sacrifice. Yet, even in the sacrifice, Kambei sees the foreshadowed end of his class. Four of the seven samurai are killed in the battle. Not a single one is defeated by the sword or spear, dying the death of a true samurai; all four are killed by gunshots. Kyuzo, the most skillful of them all, is shot in the back and dies an ignominious death in the mud.

At the very end, when the bandits have been defeated and the village saved, Kambei comes to the realization:

Kambei Shimada: In the end we’ve lost this battle, too.

[Shichiroji looks puzzled at Kambei]

Kambei Shimada: I mean, the victory belongs to those peasants, not to us.

The farmers are sowing, accompanied by music and dance. They are happy. Life will go on. They have won their victory. The remaining samurai, on the other hand, are left masterless wanderers, prisoners of their class. “Interestingly, those who beat the drums and sing are those who were recognized by the samurai as having become brave fighters during the battle scenes. Still earlier, they were the ones who ate millet and suffered hunger while they cooked and fed the samurai steamy white rice. The farmers are now organized, happy, hard-working, etc. In other words, they are behaving in such a way that you would expect them to fight without samurai, next time there is an invasion. Thus the farmers are now able to defend themselves as well as grow food.” (Singh)

Seven Samurai is a rousing epic. But, like all classic films, it is also very much a character study. Every character learns and grows and evolves. “All of them seek something and all of them find something in the time they share in the village, though not always what they expected. They learn a good deal about what farmers are and why they are why they are. Their eyes are opened.” (Astell).

Kambei Shimada’s transformation is perhaps the most subtle, and yet he is the one who, at the end, pronounces there can be no victory for the samurai. We have seen Katsuhiro comes of age, as a warrior and a man. Gorobei has found friendshi; Kikuchiyo has found action and a sense of belonging and purpose. Kyuzo has demonstrated the perfection of his art. In a sense, Kambei Shimada is all of these characters rolled into one, demonstrating the gamut of skills and attributes of the true samurai. It is his mastery of each of these elements that allows him to lead and to bring together, not just the samurai, but the villagers into a cohesive unit. Kambei continually reminds them all –and us- that all the elements must come together if a defense is to be successful. “Selfishness will not be tolerated. You’re all in one boat,” he says. And, “He who thinks only about himself will destroy himself, too.” And, “In war, it’s teamwork that counts.”

At the same time, we can see that Kambei sees Katshuhiro as a younger version of himself – young, anxious to learn and be in the thick of the fight. At one particularly compelling point in the film Kambei talks about the sacrifices a samurai makes, only to wind up alone the end. You can see in the eyes of each of the others that they have lived this journey, and know what is ahead for Katsuhiro if he remains. Indeed, the penultimate moment of the film comes after the victory over the bandits, while the farmers and celebrating and planting their crops; Katsuhiro meets his lover Shino on the road… and she casts down her eyes ignores him and moves on. Kambei Shimada sees himself, alone on the road again, his cast preventing him from ever joining the peasants in their victory.

In this way, Kambei Shimada’s journey is the opposite of Rick Blaine’s. Blaine discovers his ideals again and walks off into the night en route to rejoining a cause with renewed purpose. Kambei Shimada follows the ideals his peers have abandoned and discovers that his purpose is ultimately bereft of meaning.

Had Kambei been a different person, he could easily have ignored the peasant’s pleas. Many other samurai did. He could, like so many other samurai, have abandoned his code and taken to using his strength and skills for his own benefit alone. But such is not in his character. To the end, he exhibits the quiet nobility of a dying code of honor that will forever doom him to remain apart.

Roger O. Thornhill: “The art of survival.”

The hero of North by Northwest is reluctant, to say the least. After being mistaken for a non-existent secret agent and accused of a murder he didn’t commit, Thornhill is running for his life.

We first meet Thornhill as a successful Madison Avenue advertising executive. Self-assured in a gray flannel suit, “the classic ad-man is rushing to a business luncheon, coming down an elevator and walking briskly through a modern Manhattan office building to a taxi. Brash, smart, fast-talking, with an air of overconfidence and exuding masterful control over his environment.” (Filmsite).

Thornhill soon loses all control over his life, however, when two thugs mistake him for George Kaplan, a federal agent on the trail of a traitor smuggling government secrets out of the country. Kidnapped, he is set up for a fatal accident that he manages to escape though no real skill of his own (and only because, as we have previously learned, Thornhill is a man who can hold his liquor). Thornhill tries to regain control by tracking down the man he was mistaken for… only to reconfirm in the minds of his kidnappers that he is indeed the illusive Mr. Kaplan. Matters take a turn for the worse when, in an effort to confront the mastermind of his kidnapping he winds up the prime (and very convincing) suspect in the murder to a United Nations official. Up to this point the word ‘hapless’ describes Roget Thornhill. He escapes only through happenstance and, despite the danger he is in, is a comic figure (click the image to watch the scene):

Following the only lead he has to redeem himself, Thornhill winds up on a train to Chicago and meets Eve Kendall, a seductive woman who seems eager to help this fugitive escape. We now see Thornhill confirm what we have known from the opening scene: he has a problem with commitment. He has two ex-wives and is a playboy who has his secretary send cards and gifts to his lovers, but can’t remember what he has said to them.

In Kendall he meets his match:

Roger: Oh, you’re that type.

Eve: What type?

Roger: Honest.

Eve: Not really.

Roger: Good, because honest women frighten me.

Eve: Why?

Roger: I don’t know. Somehow they seem to put me at a disadvantage.

Eve: Because you’re not honest with them?

Roger: Exactly.

It is no coincidence that when Thornhill gives his matchbook to Eve, he notes that his initials spell ‘rot.’ He is intelligent and witty and charming; he displays the ad man’s lack of scruples and uses his skills to no higher purpose.

But the ad man gets played. Kendall, it turns out, is really the mistress of the evil kidnapper-mastermind, Philip Vandamm. She pretends to help him arrange a meeting with the real George Kaplan, but in reality sends him into an ambush (the cropduster attack, one of the most iconic scenes in thriller history – click on the image to see it).

Thornhill escapes once again. In this scene -confronting danger in a wide open space where a man should seemingly have nothing to fear, Thornhill begins his transformation. He returns to Chicago, and tracks Eve and Vandamm to an art auction, where he confronts them publicly:

“What possessed you,” asks Vandamm, “to come blundering in here like this? Could it be an overpowering interest in art?”

“Yes,” Thornhill replies. “The art of survival.”

(Click on the image to watch the scene.)

Thornhill would not recognize it, because he is acting as circumstances dictate he must in order to stay alive, but he is gradually becoming the clever secret agent, George Kaplan. It happens at first in the minds of his pursuers, who interpret every hairsbreadth escape and accidental discovery as the work of a highly-trained counterespionage agent. But as his peril increases and he experiences personal betrayal at the hands of Eve, Thornhill adopts the relentless intelligence of a man such as Kaplan would be… if he existed.

And then… we discover Eve Kendall really is a government agent. Thornhill, during his confrontation at the art gallery, has jeopardized her cover. When the Professor asks him to continue playing Kaplan, at first her refuses: “I’m an advertising man, not a red herring.”

But realizing the woman he has come to care for is in danger, he agrees. Later, after a charade in which Eve Kendall is allowed to “shoot” Kaplan to vindicate herself in the eyes of Vandamm, Roger and Eve meet. He asks her how she got into this situation.

Eve: “It was the first time anyone ever asked me to do anything worthwhile.”

Roger: “Has life been like that?”

She reveals that she is the result of failed relationships with men who only sought to take advantage of her, that what happened in her life is,“Men like you.”

“What’s wrong with men like me?” Thornhill asks.

“They don’t believe in marriage.”

Roger tells Eve he will set things right after Vandamm is away. She has captured his heart and he is ready to commit. Only to discover that Eve has been assigned to accompany Vandamm. The Professor says it’s something she ‘has to do.’ Thornhill is incensed.

‘Nobody has to do anything,” rails Thornhill. “I don’t like the games you play, professor.” This calls to mind the fact that we first saw the Professor and his colleagues playing fast and loose with human lives, including Thornhill’s, over a Washington conference table. “If you fellas can’t lick the Van Dammes of the world without asking girls like her to bed down with them and fly away with them and probably never come back, perhaps you ought to start learning how to lose a few cold wars.” It is at this point in the film -realizing that he has been lied to and that Eve, despite her belief she is working for good, is simply being used once again by the noncommittal- that George Thornhill literally does turns him into Kaplan. He becomes an agent on a mission of purpose to rescue the girl he has fallen in love with. What follows is a man transformed into something out of a Bond film, escaping through windows, climbing stone walls, eluding killers in a deadly chase across the top of Mount Rushmore.

Thornhill’s efforts to escape assassination, discover why he is being pursued and clear his name are the initial driving force in the film. But along the way Thornhill, like Blaine and Kambei Shimada, finds purpose and ideal. He discovers love and commitment, and also a sense of justice, outraged that the forces of right and good would stoop to using a woman as a pawn.

Initially, Thornhill has no choice but to act for self preservation. But when he is given choices, he is no longer the non-committal, truth-avoiding playboy. Like Kambei Shimada and Rick Blaine, he has become a crusader for justice, willing to risk his life, not just for a woman (although in this case a happy-ending romance is more central to the theme) but also for an ideal of justice and right.

In each of these classic films the central character takes in inner journey to discover purpose and learn the nature of idealism and sacrifice. Each is transformed in the process and will never be the same again. Each as we leave them is embarking on another journey…

References:

Astell, H. (n.d.) Seven Samurai. Retrieved May 22, 2011 from http://www.apocalypselaterfilm.com/2010/01/seven-samurai-1954.html

Casablanca. (n.d.) Filmsite movie review: Casablanca (1942) Retrieved May 22, 2011 from http://www.filmsite.org/casa.html

Coleman, H. (Producer) & Hitchcock, A. (Director). (1959). North By Northwest. (USA). Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Morrow, L. (1982, December 27) Essay: We’ll always have Casablanca. Time Magazine. Retrieved May 22, 2011 from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,923243-2,00.html#ixzz1N7KPMV3F

Motoke, S. (Producer) & Kurosawa, A. (Director). (1952). Seven Samurai. Japan: Toho

North By Northwest. (n.d.) Filmsite movie review, North by Northwest (1959). Retrieved May 22, 2011 from http://www.filmsite.org/nbnw.html

Oriental Outpost (n.d.) Bushido virtues: the way of the samurain. Retrieved May 22, 2011 from http://www.orientaloutpost.com/bushido-code-of-the-samurai.php

Singh, A. (2003, October) Kojeve’s masters and slaves, Kurosawa’s samurai and farmers. Film Philosophy. Retrieved May 22, 2011 from http://www.film-philosophy.com/vol7-2003/n34singh

Wallis, H. (Producer) & Curtiz, M. (Director). Casablanca. (1942). USA: Warner Brothers